Beyond the familiar names is a world of obscure art movements that once burned brightly before fading away. These forgotten styles helped shape the evolution of modern art, influencing everything from abstract painting to contemporary design.

Why do some artistic revolutions stand the test of time while others vanish? Their stories tell us about shifting cultural tides. Some were too radical for their era, others were overshadowed by new trends, and many simply never gained widespread recognition outside their origins.

The impacts of these overlooked art movements can be found in everything from avant-garde typography to street art. Exploring them doesn’t just expand our understanding of artistic innovation—it uncovers the forces that helped shape what we consider “great” art today.

1. Peredvizhniki – The Wanderers

Revolution against established art institutions isn’t unusual in the histories of art. One group, however, went even further. Not only did they reject the constraints of the Imperial Academy of Arts, they decided to take their art to the people, organising traveling exhibitions. They travelled across Russia under the (uncreative) name of the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions. They became known as the Peredvizhniki, often translated as The Wanderers.

Their paintings depicted rural scenes, farmers, peasants and the countryside. But their rebellion was not just aesthetic—it was deeply political. While western European art would show the peasant as noble, the Peredvizhniki focused their art on the struggles of peasantry and the harsh reality of forced manual labour. This, in the background of the abolition of serfdom in 1861.

What makes the work of the Peredvizhniki even more interesting is that these brutal scenes are rendered beautifully against a gorgeous backdrop of the Russian countryside. Take, for example, Ilya Repin’s Barge Haulers on the Volga (1873) or Grigoriy Myasoyedov’s Busy Time for the Mowers (1887). At first glance, their work looks almost romantic – such as Jean-François Millet or Jules Bastien-Lepage. But look closer and you see the suffering is not noble. It is a reminder of the brutality peasants used to face under serfdom.

Yet, the beautiful representations of these scenes bled into the Russian identity. Their landscapes would influence the later Russian Impressionists. They helped shape the visual language of Russian Identity. Their insistence on art as a means of social engagement directly influenced the Soviet Realist style – whether you think that’s a good thing or not.

So with such an influence, is it obscure? It is perhaps somewhat forgotten or under-appreciated due to its strong political nature – perhaps dismissed somewhat as propaganda.

Art that gets too political can often become dismissed. There is perhaps a notion that art should be pure. Couple this with the fact that’s its influence and popularity did not spread far from Russia and we think that’s it’s not appreciated as it should be.

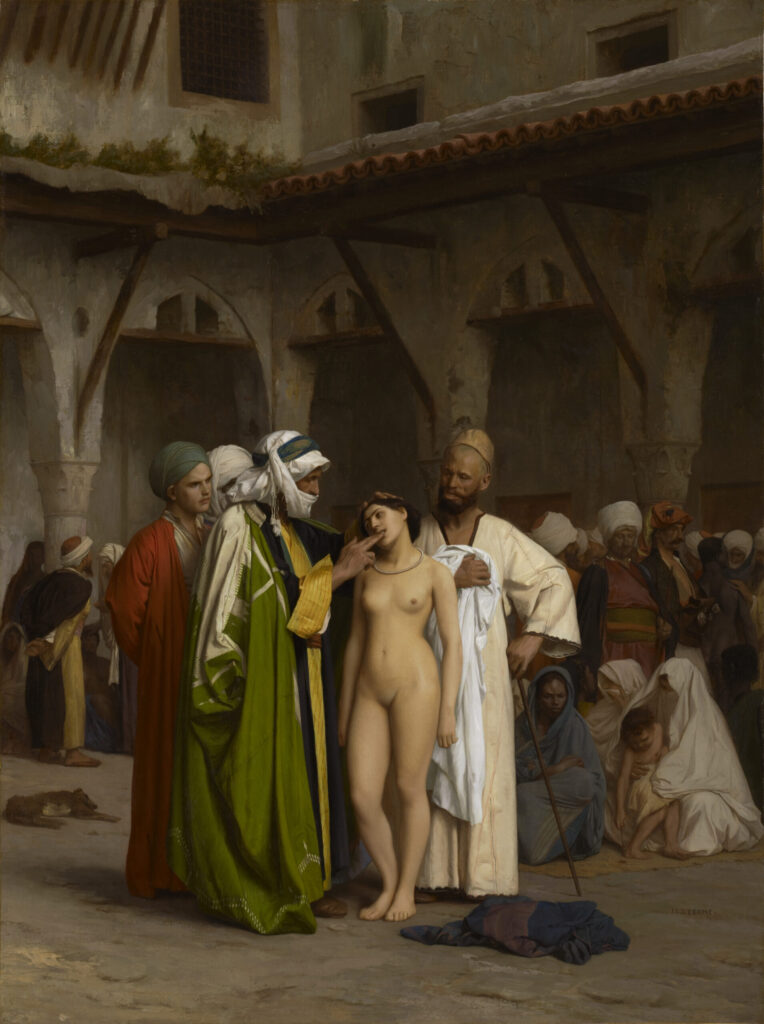

2. Academic Orientalism

It is entirely possible for realist and nationalist art form to have a negative effect on cultural identity. Academic Orientalism is a perfect example of this.

Throughout the 19th century, European painters fixated on the mystique of the “Orient”, a broad and often misleading term used to describe the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia. It should already be obvious you are heading into murky waters when so many separate cultures are grouped in such a way.

Academic Orientalism blended Romanticism’s exoticism with Neoclassicism’s precision. It had lavish depictions of harems, desert landscapes, and bustling bazaars – mostly entirely made up. Artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, and John Frederick Lewis portrayed these scenes with extraordinary detail, yet often through a Western gaze that reinforced stereotypes and imperialist fantasies.

A great example is the John Singer Sargent painting shown above – aesthetically beautiful and skilfully executed. Culturally, however, it is a conglomeration of artefacts from all across North Africa.

While enormously popular at the time, Academic Orientalism fell into decline in the early 20th century as modernism rejected its theatrical realism and colonial overtones. Today, the movement remains both controversial and influential. On one hand, criticized for its romanticized distortions of non-Western cultures, yet on the other, recognized for its technical mastery and impact on visual storytelling. Its legacy lingers from Hollywood films to high fashion editorials, making it a movement both obsolete and enduring.

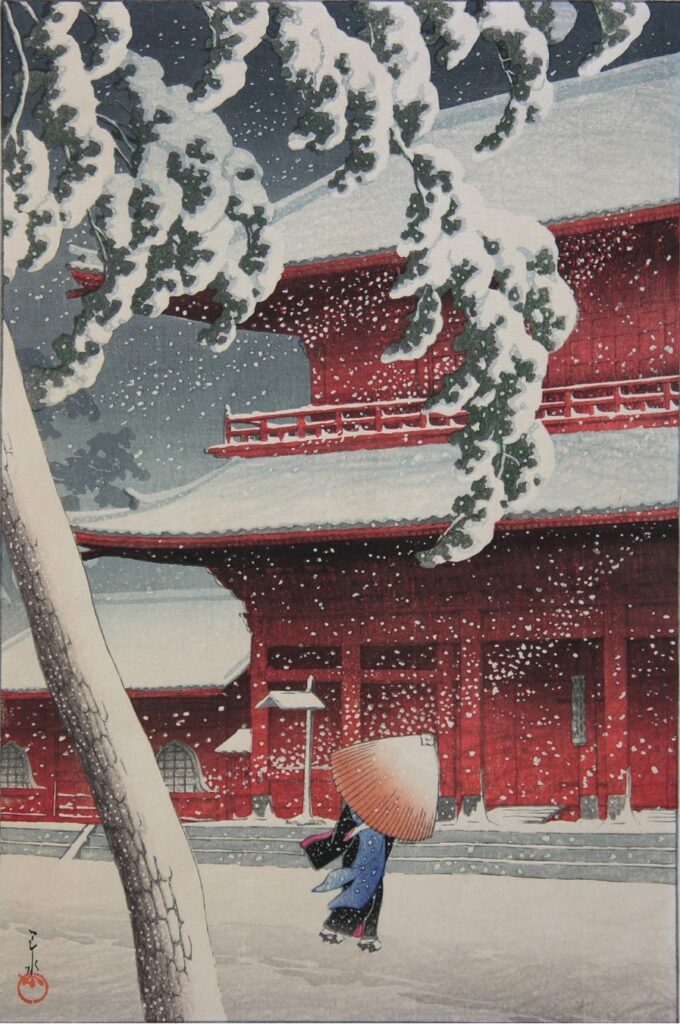

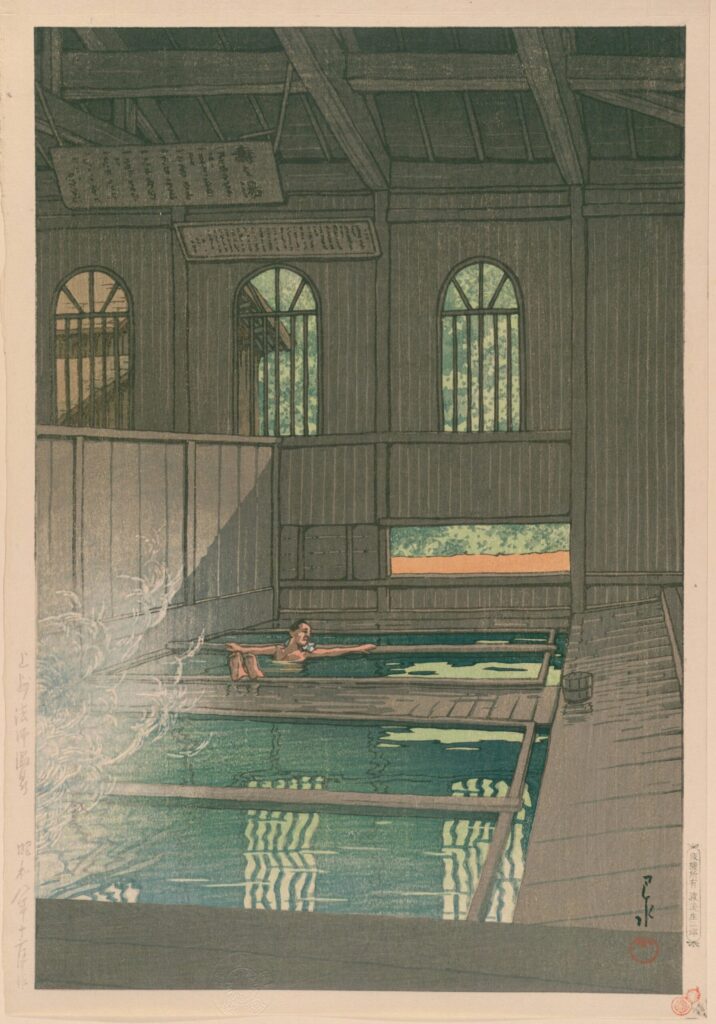

3. Shin-hanga

From series Twenty Views of Tōkyō.

Sometimes the truest cultural identity comes from looking back at the art history of one’s own culture. This is what the Shin-Hanga artists of early 20th-century Japan did. They sought to revitalise the traditional ukiyo-e woodblock print but modernise it by including techniques such as realism, shading and atmospheric lighting. While ukiyo-e was highly stylised, the Shin-hanga artists aimed for subtlety and a painterly quality.

The movement was largely driven by publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō, who collaborated with artists such as Kawase Hasui, Hashiguchi Goyō, and Itō Shinsui. They produced prints that featured landscapes, beautiful women (bijin-ga), kabuki actors, and nature scenes. Though Shin-Hanga prints gained widespread popularity in the West, they struggled to achieve the same recognition within Japan. Here, avant-garde movements were gaining ground. As Japan modernized, artistic priorities shifted, and the collaborative workshop model on which Shin-Hanga depended became increasingly difficult to sustain. The rise of Sōsaku-Hanga (“Creative Prints”), which emphasized individual artistic expression rather than traditional division of labor, further contributed to its decline.

Following World War II, the movement faded further as Japan’s focus turned to industrialization. Western collectors—once a major source of demand—became more interested in contemporary abstract art. At the same time, the number of skilled artisans who specialized in traditional printmaking dwindled. Though overshadowed for much of the late 20th century, Shin-Hanga has seen a revival in recent decades, with collectors and museums recognizing its value. However, compared to the more famous ukiyo-e era, Shin-Hanga remains relatively obscure in broader art history.

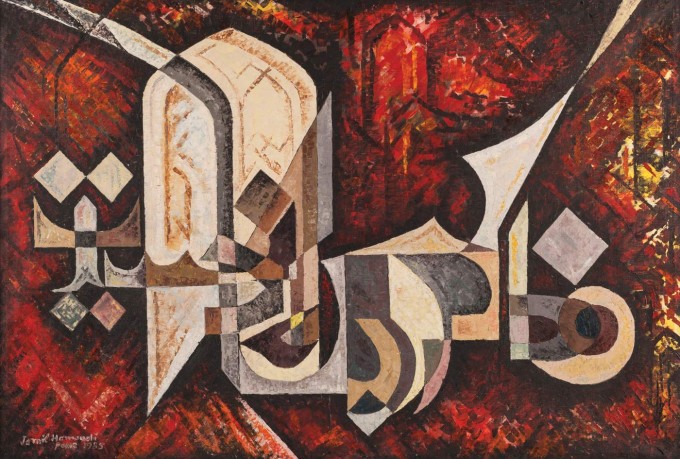

4. Hurufiyya

Source

Another art movement, like Shin-Hanga, which looked inward for inspiration whilst simultaneously connecting to modern artistic ideas, was Hurufiyya. This was a movement that reimagined Arabic calligraphy as a visual, abstract form, not only just a tool for writing. By experimenting with the shapes, rhythm, and composition of letters, Hurufiyya artists created a unique style that blurred the line between traditional Islamic art and modern abstraction.

For some artists, such as Shakir Hassan Al Said, this fusion was a deliberate effort to create a modern Arab aesthetic while still drawing from cultural heritage. Others, like Rachid Koraïchi, were more focused on the expressive and abstract potential of Arabic script itself. Regardless of intent, Hurufiyya stood apart from both Western modernism and traditional calligraphy, forming a distinct artistic movement that emphasized the fluidity, dynamism, and sculptural quality of letters.

Hurufiyya was particularly influential in the Arab world, Iran, and Türkiye, with artists integrating calligraphy into canvases filled with bold colours, gestural brushwork, and layered textures. Though widely exhibited in the Middle East and North Africa, the movement remains relatively obscure in Western art history, often overshadowed by European and American abstract movements. However, its impact endures in contemporary Middle Eastern art.

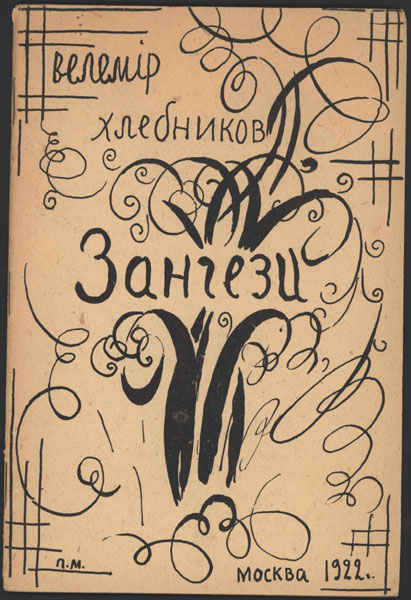

5. Zaum

If Hurufiyya had the effect of stripping language of its inherent meaning in favour of a focus on the visual effect of the abstract shapes, Zaum took this even further.

Coined by poets Aleksei Kruchyonykh and Velimir Khlebnikov, the term translates loosely to “beyond the mind”, reflecting the movement’s attempt to create a transrational, universal language that transcended logic, national identity, and conventional meaning. Zaum was not just a literary movement—it extended into theater, painting, and typography.

Zaum’s influence on visual art was particularly striking. Many of its pioneers believed that language and images were intertwined. They believed breaking words down into pure sound and form was akin to the reduction happening in Cubism and Suprematism. Kruchyonykh, for example, incorporated abstract calligraphy, nonsensical scripts, and dynamic layouts into his handwritten and printed works. This approach resonated with Russian Futurist painters, who sought to depict movement and energy beyond literal representation. Malevich’s Suprematist compositions can be seen as a pictorial equivalent of Zaum’s linguistic experiments.

Though Zaum never became a fully realized linguistic system, its values closely aligned with Futurism and Dada. Its rejection of traditional structure left an enduring mark on performance art, experimental poetry, and sound-based visual design. Today, while largely obscure outside academic circles, Zaum’s legacy persists in conceptual art, avant-garde typography, and even the visual manipulation of text in contemporary graphic design.

6. Rayonism

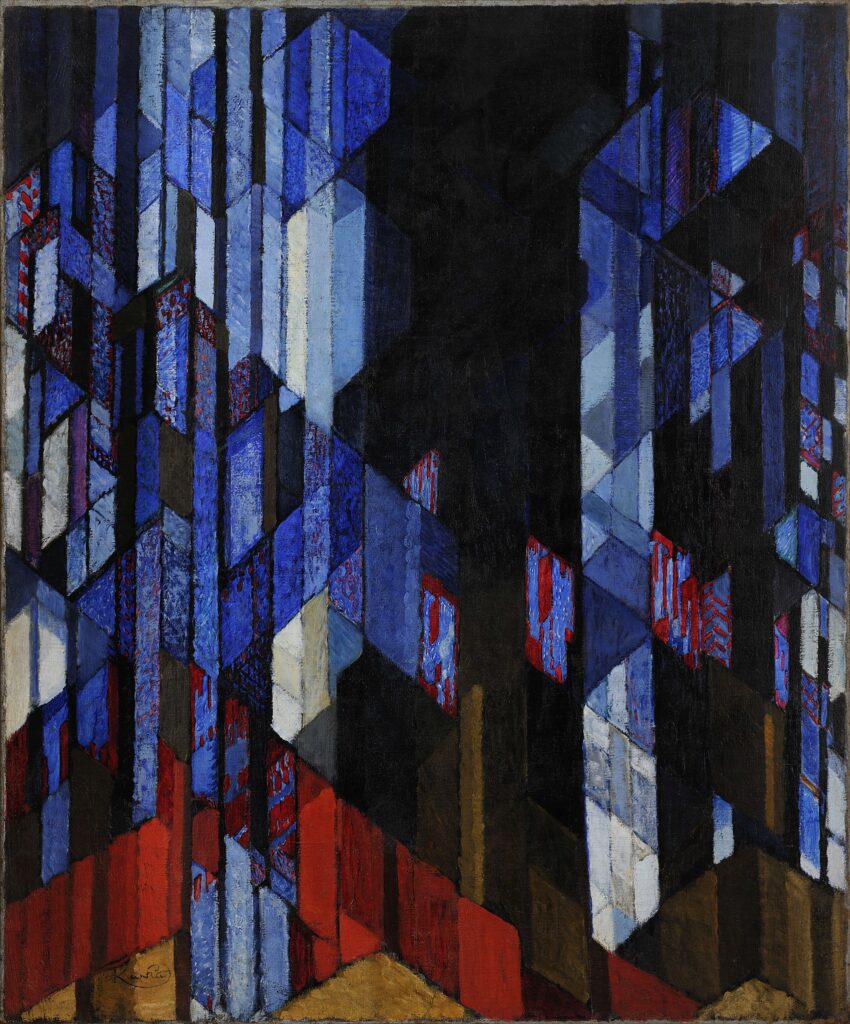

Around a similar time in Russia, Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova founded another abstract and experimental art form. Like Zaum, its process was the abstraction of something literal into a form unrecognisable from it.

Termed Rayonism, it was a short-lived yet ground-breaking movement that sought to capture the dynamic interplay of light, energy, and space. It was heavily influenced by Cubism, Futurism, and the contemporary scientific discoveries related to X-rays and electromagnetic waves. Rather than depicting physical objects, Rayonist painters aimed to show the rays of light reflecting off surfaces, breaking down forms into intersecting beams and fragmented lines.

Rayonism holds a significant place in the history of abstraction, as it was one of the earliest purely abstract movements. While Cubism and Futurism still retained recognizable forms, Rayonist paintings often contained no identifiable subject matter.

In contrast to the rigid geometry of Suprematism and Constructivism, Rayonist works had a more expressive and chaotic quality, resembling a fusion of Impressionist light studies and the fractured perspectives of Cubism. Paintings like Larionov’s Red Rayonism (1913) or Goncharova’s “The Cyclist (1913) explode with angular, intersecting lines, suggesting motion and force rather than tangible forms.

Though the movement was brief and overshadowed by later Russian avant-garde styles, its radical approach continues to resonate in contemporary and immersive digital art.

7. Orphism

Also at a similar time, an abstract movement was beginning in France. Orphism began as a vibrant offshoot of Cubism, emphasizing pure abstraction, dynamic colour, and the sensation of movement. Orphism sought to liberate colour from form, much like music is independent of narrative meaning. The movement’s leading figures, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, created compositions that abandoned linear perspective in favour of rhythmic colour harmonies.

Unlike Cubism, which often employed a muted, analytical approach to form, Orphist paintings burst with vivid colors and circular, swirling compositions. Works such as Robert Delaunay’s “Simultaneous Windows” (1912) and “The First Disc” (1913) or Sonia Delaunay’s textile designs convey a sense of motion.

Despite its brief existence, Orphism played a crucial role in bridging Cubism and later forms of abstraction. It influenced movements like Futurism, Abstract Expressionism, and Op Art, where the focus on colour interaction and perception became central concerns. Orphism as a distinct movement faded by the mid-1910s, making it both foundational and now somewhat obscure.

8. Concretism

Source

Emerging in the 1930s and 1940s, Concretism took the abstract approach even further. It represented a radical departure from previous artistic traditions, which stands out even in the context of this article. Concretism advocated for pure abstraction based entirely on geometric shapes and mathematical order.

The term was first formalized by the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg in 1930, when he outlined its principles as a rejection of symbolism, illusion, and subjective interpretation. For him, art was to be entirely self-referential, a reality in itself rather than representing anything from the external world.

Unlike earlier abstract movements like Rayonism and Orphism, which retained elements of spontaneity and expressive color, Concretism was highly systematic and rational. It found its strongest expression in Switzerland and South America, including artists such as Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse, and Joaquín Torres-García. Works from this movement typically feature hard-edged geometry, precise grids, and mathematical proportions. Concrete art compositions feel engineered rather than painted.

Concretism has had a lasting impact on Minimalism and modern graphic design. Its principles can still be seen in corporate branding, architecture, and digital aesthetics today. However, the movement remains overshadowed by more expressive forms of abstraction, making it an influential yet somewhat obscure force in the history of modern art.

9. CoBrA

Source

Movements like Concretism pushed the boundaries of minimalism and cold geometric modernism, and Cobra can be seen as an antithesis to this.

CoBrA appeared later, in 1948. It was short-lived but highly influential. CoBrA championed raw, instinctive and rebellious expression in art. The name is from the cities of its founding members: Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. CoBrA rejected both academic formalism and the refined spontaneity of Tachisme. Instead of focusing on abstract mark-making, CoBrA artists sought to create visceral, emotionally charged imagery. They drew on folk traditions, children’s drawings, and Art Brut (outsider art) to develop a bold, figurative style.

The movement’s leading figures, including Karel Appel, Asger Jorn, Constant Nieuwenhuys, and Corneille, embraced a deliberately chaotic, primal aesthetic. Their works featured distorted human and animal figures, aggressive brushstrokes, and thick, rough textures. It reflected a desire to break free from post-war cultural constraints. Unlike the lyrical abstraction of Tachisme, which was often introspective and fluid, CoBrA paintings had a confrontational, almost anarchic energy.

Though CoBrA lasted only three years (1948–1951) as an organized movement, its influence was significant, particularly in Neo-Expressionism, Art Brut, and even contemporary street art. However, outside specialized art circles, CoBrA remains relatively obscure, often overshadowed by the American and French abstract movements.

10. Tachisme

Emerging in postwar France in the 1940s and 1950s, Tachisme (from the French tache, meaning “stain” or “blot”) was a spontaneous, gestural painting style often considered the European counterpart to American Abstract Expressionism. Tachisme artists rejected the structured compositions of Cubism and the cold rationality of geometric abstraction. Instead, they embraced intuitive, free-flowing brushwork, drips, and irregular forms.

Leading figures such as Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Soulages, and Hans Hartung emphasized the physicality of paint, treating the act of painting as a direct expression of emotion and subconscious energy. This aligned Tachisme with Surrealist automatism. Unlike the bold, aggressive gestures of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, however, Tachisme often had a more lyrical, delicate quality, with softer, more organic forms.

Although Tachisme was highly influential in European post-war modernism, it was eventually overshadowed by the dominance of American Abstract Expressionism in the international art world. Today, it remains less widely recognized, despite its critical role in shaping Informalism and later experimental approaches to painting.

Leave a Reply