This post examines previous art movements and moments that have fallen prey to controversy, suppression and vilification to discover why art gets suppressed. In these movements we see three common justifications:

- Religious reasons

- Political reasons

- Obscenity reasons

The justifications can cause some of the most seemingly-innocent art to fall victim to suppression and fall into obscurity.

Art as Heresy: When Religion Bans Creativity

Religion has produced some fairly strong opinions on a whole range of things and one of those things in particular is art. The relationship between art and religion is certainly extensive. It could be argued we have religion to thank for a wide range of art. This is true, but also we have religion to blame for the destruction and suppression of a whole other range of art.

The interesting thing about the suppression of art in the name of religion is that it comes from both extremes. There is the scandalous and the vulgar, but there is also the art that is too close to the divine – often it is representations of god or of prophets and equally fall to religious censure.

Sacred Art in the Eastern Christian World

One of the most infamous waves of religious censorship was Byzantine Iconoclasm, a movement that banned and destroyed religious icons across the Eastern Christian world. Iconoclasts believed that worshipping painted or sculpted images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints was idolatrous, violating the Second Commandment.

During this movement:

- Monasteries were raided, frescoes scraped from walls, and thousands of sacred icons burned or smashed.

- The Hagia Sophia, once covered in detailed mosaics of Christ, was stripped bare, leaving only simple crosses in their place.

- Surviving icons from this period exist today only because devout monks hid them in remote monasteries, such as St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, where ancient Byzantine icons were rediscovered centuries later.

Nina Aldin Thune

Mosaics of Jesus do not seem like the most scandalous or risque art pieces, but this is a great example of the power of images and the meaning in art – and how, with concentrated sources of power, any art can become dangerous.

Catholic Imagery during the Protestant Reformation

Another such example is when, in the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation ignited another wave of iconoclasm. This time Catholic religious art was the target. Reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin saw elaborate altarpieces, gilded sculptures, and murals as distractions from true faith. As Protestantism spread, so did destruction. During this movement:

- In the Netherlands, England, and parts of Germany, entire churches were stripped of their artwork.

- Stained glass windows, medieval frescoes, and statues of saints were smashed, burned, or removed.

- One of the most dramatic losses was Hans Holbein the Elder’s altarpiece in Augsburg, which was destroyed during anti-Catholic purges.

- England’s Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–1541) saw the looting and demolition of monastic churches, along with their centuries-old artworks.

The irony is that some Catholic art survived not because it was accepted, but because it was repurposed: churches whitewashed murals instead of removing them, unknowingly preserving them beneath layers of paint that would later be rediscovered.

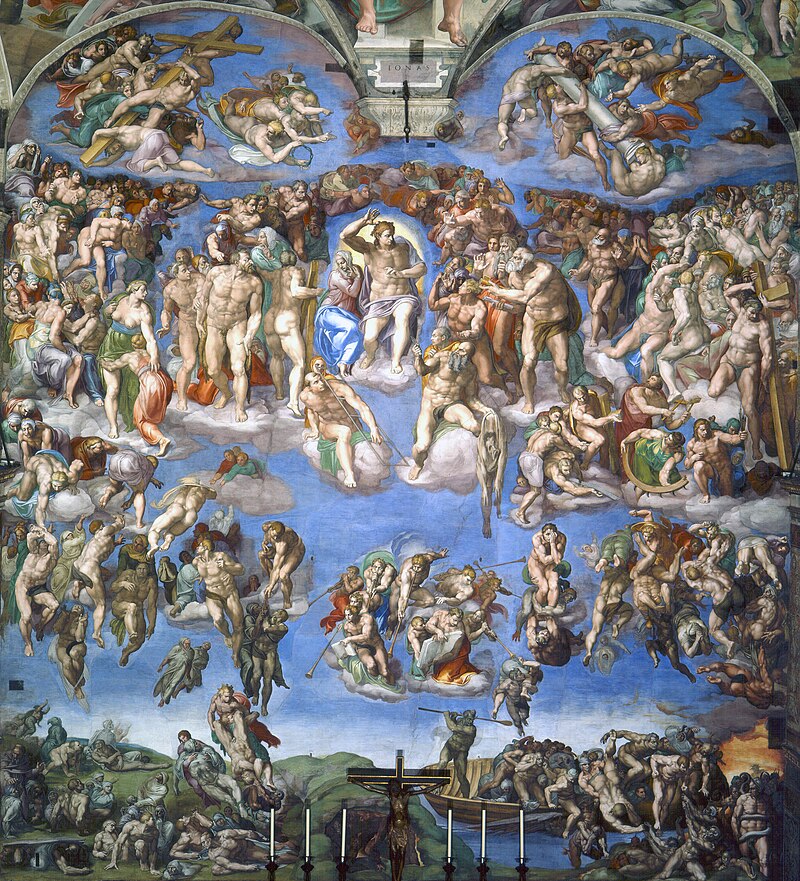

Michelangelo’s Censored Nudes in the Sistine Chapel

Even work commissioned by the church itself, from one of their key artists was not necessarily safe. Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment (1536–1541), painted in the Sistine Chapel, scandalized the Vatican because of its realistic nude figures. He was accused of indecency and sacrilege as a result.

In response, Pope Paul IV ordered the genitals covered, leading to Daniele da Volterra painting draped cloths over the figures, earning him the nickname Il Braghettone (The Breeches Maker).

In later centuries, restoration efforts attempted to remove the censorship, revealing Michelangelo’s original vision.

Caravaggio’s Banned Paintings: Too Real for the Church

The Baroque master Caravaggio (1571–1610) was a revolutionary artist who used ordinary people as models for sacred figures, depicting them with gritty realism rather than idealized beauty. His work often offended religious authorities, leading to outright rejections. Some of his paintings which struck the ire of the church include:

- Death of the Virgin (1606): Commissioned for a Carmelite church, this painting of Mary’s deathbed was rejected because she looked too human—pale, bloated, and undignified.

- Saint Matthew and the Angel (1602): Originally commissioned for a chapel, this painting showed a barefoot, rough-looking Saint Matthew being guided by an angel, which was deemed disrespectful. It was rejected and replaced with a more conventional version.

While Caravaggio’s work was dismissed at the time, his radical approach later influenced countless artists, proving that religious censorship could not erase artistic progress.

The Taliban and the Bamiyan Buddhas

Religious art destruction isn’t just a relic of the past. In 2001, the Afghan Taliban systematically destroyed the Bamiyan Buddhas, massive 6th-century statues carved into a cliffside, declaring them idolatrous and un-Islamic.

The destruction was an act of cultural and religious erasure, eradicating an ancient Buddhist presence in the region. It may be argued this has political causes also, but the mechanism which justified the destruction was religious.

Unlike frescos in English monasteries, there was no layer of paint to remove and gaze upon the artwork – they were reduced to rubble. However, since then digital reconstructions and 3D holograms now attempt to restore what was lost, showing how modern technology is used to resist religious censorship.

Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987)

These examples so far could be seen as fairly innocent art that has fallen under religious suppression almost from bad luck. But what about art that is purposefully offensive?

One of the most infamous examples is Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, a photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine.

The piece provoked outrage, vandalism, and even death threats, with politicians and religious groups condemning it as blasphemy.

Some galleries that exhibited the piece faced violent attacks and pressure to remove it.

Without argument, this is the most offensive example on this list, but it is interesting how in a modern multicultural society, it has a better chance of being saved than a painting of Mary, because she didn’t look pure and perfect enough.

Art as a Political Threat: Censorship by Governments and Regimes

Art can say a lot regardless of whether it is symbolic, realistic, romantic, impressionistic abstract or just about anything else. Even if it’s not saying anything, it can still elicit powerful emotional responses (consider Saturn Devouring his Son by Goya or Guernica by Picasso). Art is almost expected to have layers of meaning placed upon it. And art also has plausible deniability and ambiguity.

As such, art has been feared by anyone with a singular agenda. Often that can be those in power and those that want to stay in power. Artists have the ability to challenge this authority, expose corruption and inspire dissent.

It is not only art that is suppressed but artists also. It is not only totalitarian regimes by democratic governments also. But one thing is common: history shows that the more regimes try to erase politically dangerous art, the more it takes on a life of its own

The Power and Peril of Political Art

Before the internet, societies required organisational mechanisms. How do you create a movement? How do you gather like-minded people? How do you distribute messages and new ideas? Like religion, art can act as one of these organising mechanisms.

Art is a weapon of influence, capable of mobilizing resistance, redefining national identity (consider the Australian Impressionists), and exposing oppression. Governments throughout history have recognized this power and have responded in one of two ways: co-opting art for propaganda or attempting to suppress it entirely.

Political art is targeted for several reasons:

- It criticizes the ruling class – Satirical, anti-government, or revolutionary art often depicts leaders in an unflattering light.

- It exposes state crimes or failures – Art can document human rights abuses, economic failures, or war atrocities.

- It glorifies opposing ideologies – Art that promotes democratic ideals in an authoritarian state (or vice versa) is often erased.

- It inspires rebellion – Art is a rallying point for movements that challenge political power, from anti-colonial struggles to labor rights campaigns.

Despite the efforts to suppress or destroy these kinds of artworks, political art often resurfaces in underground movements, hidden archives, or later historical revivals.

The Avant-Garde in the Soviet Union

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, radical modernist art movements like Constructivism and Suprematism flourished under Lenin’s early Bolshevik rule. Artists like Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky believed art could shape the revolutionary future, using bold abstraction and geometric forms to break from the past.

Constructivism actively supported propaganda and the entire movement itself existed to perpetuate a certain idea of an industrial, socialist future.

However, under Stalin in the 1930s, these movements were branded “bourgeois” and anti-revolutionary.

Socialist Realism became the only acceptable style, glorifying workers, industrial progress, and Soviet leaders. Avant-garde artists were silenced. Even Constructivism – itself essentially Soviet propaganda, fell prey to this. To those in power, there could be no competing narratives – even narratives that supported many of the same ideals.

Modernist artworks were hidden in archives or destroyed. Soviet museums purged their collections. These collections were, at one stage, a revolutionary tool but after the revolution was established, they became a liability.

The final irony is that Socialist Realism, at least to the western world, had become quite obscure. It’s likely that critics and connoisseurs dismiss highly politically-enforced art movements yet it would seem there is a difference as to whether it is the state itself driving these movements or whether they happened more naturally.

Nazi Germany War on “Degenerate Art”

During Nazi Germany we saw a government try and outlaw some of the most famous and well-known artists. At the time and place, they were somewhat successful, but this impact only really lasted as long as their reign.

In place of modern art, Hitler promoted “heroic realism,” a propagandist style, not dissimilar to Socialist Realism, that glorified Aryan ideals and military power.

To solidify the idea that modernism was corrupt and anti-German, the government held a “degenerate art exhibition.” The intent was to mock and discredit these artists. The irony is that, given some of the names of painters exhibited, it was likely a very beautiful exhibition containing works from Picasso, Mondrian and Kandinsky.But the exhibition was only the focal point of a larger campaign. In total more that 16,000 artworks were seized from German museums – some destroyed and some secretly sold abroad. While much of this art was lost, some works survived—either hidden by curators or resurfacing after the war. Today, pieces once labeled “degenerate” define modern art history.

Mao’s Cultural Revolution: An entire milieu under fire

The manner in which authoritarian regimes suppress art seems to repeat despite the time and place. Above, we see similarities between The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany and a similar line can be seen during China’s Cultural Revolution.

Similarly, much associated with China’s pre-communist past or Western influence was suppressed or destroyed. Again, there was an exhibition, staged to mock and discredit. In China they were called the “Black Paintings” and the entire art circle in mainland China was implicated.

Although the Black Paintings controversy gradually settled down upon Mao’s disagreement with the movement, much was still lost during the Cultural Revolution.

The United States’ Red Scare: Anything that could almost possible conceivably be linked to communism in any way shape or form

Censorship isn’t exclusive to totalitarian regimes. During the McCarthy era (1940s–50s), American artists suspected of Communist ties faced blacklisting, FBI surveillance, and professional ruin.

- Diego Rivera’s Rockefeller Center mural was destroyed because it included a portrait of Lenin.

- Filmmakers and playwrights, such as Dalton Trumbo, were blacklisted for alleged Communist sympathies.

- Government-funded exhibitions avoided politically charged themes to prevent backlash.

While democratic censorship is often more economic than physical, it can still effectively erase politically inconvenient artists from public life.

Modern Political Censorship: The Art of Ai Weiwei

In contemporary China, artist Ai Weiwei has been repeatedly targeted for his politically charged works.

- His installation “Remembering” criticized the government’s handling of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.

- His studio was demolished, and he was briefly imprisoned in 2011.

- His exhibitions have been banned in China, though his work reaches global audiences.

Ai Weiwei exemplifies how artistic dissent persists despite state censorship, often finding new life beyond borders.

Too Explicit to Survive: Art Suppressed in the Name of Modesty

Art has always pushed the boundaries of what is socially acceptable, and few subjects have been more contested than nudity, sexuality, and the human body. From religious morality to government obscenity laws, explicit art has been suppressed, defaced, and even destroyed to protect public decency—or, more often, to maintain societal control.

However, unlike political art, which is often erased for ideological reasons, erotic and sexually explicit art faces a different challenge: it survives only when it can justify its existence. If an artwork gains cultural legitimacy—through high-profile patronage, artistic movements, or sheer popularity—it can overcome controversy. But when it fails to gain that legitimacy, it risks being erased from history.

The War on the Nude: When the Human Body Became Controversial

Nude art has been central to artistic expression for millennia, yet it has never been free from controversy. Throughout history, societies have imposed restrictions on how the human body can be represented—particularly when those depictions stray into the erotic. This article explores how censorship in art has targeted nudity, the backlash faced by artists who challenged social norms, and how public morality laws shaped what could be shown, exhibited, or remembered.

Renaissance Reverence and Religious Boundaries

During the Renaissance, the nude body was not only accepted but revered, especially in religious art. Artists such as Michelangelo used the human form to express spiritual purity and divine beauty. Yet this reverence existed alongside strict boundaries.

Nineteenth-Century Contradictions: Classical Nudity vs. Erotic Realism

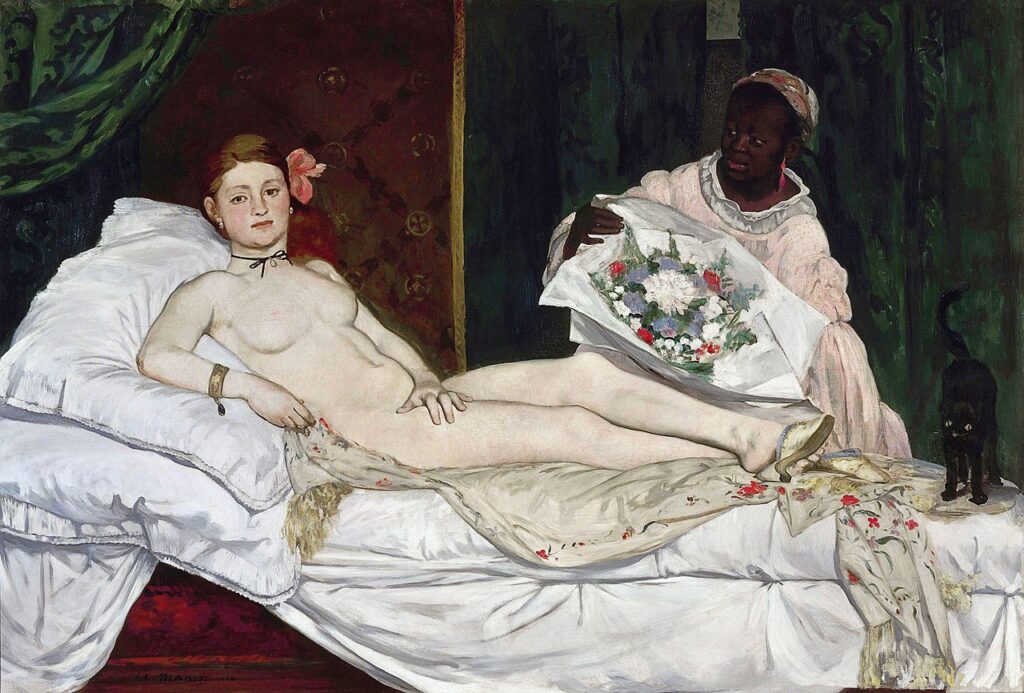

In 19th-century Europe, nudity was accepted within the framework of classical ideals. Paintings that depicted mythological or ancient subjects were often praised, even when the figures were nude. However, when contemporary artists used the nude form to portray real, modern people—especially in erotic or confrontational ways—they often faced intense criticism.

Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) was a turning point. The painting depicted a nude prostitute reclining confidently, her gaze fixed on the viewer. Unlike classical nudes, which were typically idealized and passive, Olympia was defiant and modern.

Critics were outraged. Her direct stare and urban setting were seen as vulgar. The work was nearly removed from public exhibition, and its reception was so divisive that it became one of the defining controversies of the time. Still, Olympia survived, largely thanks to Manet’s affiliation with the avant-garde movement. What saved the painting wasn’t acceptance—but the growing influence of artists willing to defy tradition.

Few works embody the tension between erotic art and censorship as starkly as Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866). The painting, a close-up of a woman’s genitals, was immediately deemed too obscene for public display.

For over a century, the painting remained in private collections, hidden behind a green curtain. It was not shown publicly until the 1990s, long after Courbet’s artistic significance had been widely acknowledged. Even today, L’Origine du Monde faces censorship: social media platforms routinely block or remove its image, demonstrating that digital spaces continue to police the boundaries of erotic art.

While Courbet’s work eventually gained legitimacy due to his historical stature, many explicit works from lesser-known artists were not so fortunate. Countless paintings, drawings, and photographs were destroyed, defaced, or quietly erased from memory.

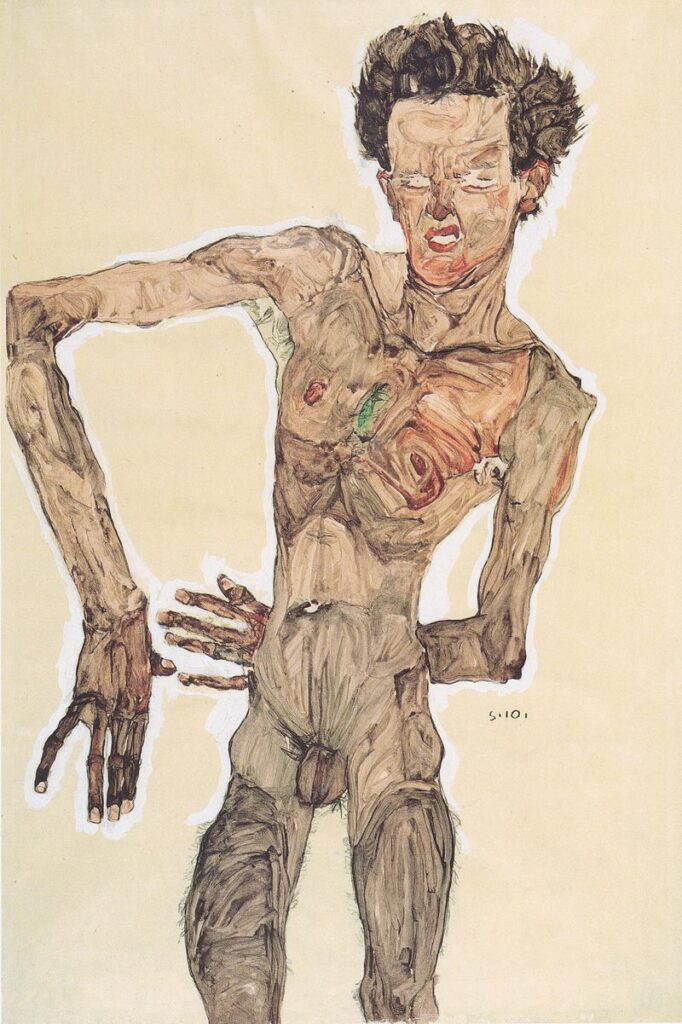

Moral Panic and the Trials of Egon Schiele

In the early 20th century, Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele emerged as one of the boldest figures in erotic art. His work was emotionally raw, often depicting gaunt, contorted figures in stark sexual poses—far from the polished elegance of academic nudes.

In 1912, Schiele was arrested and accused of producing immoral images that could corrupt minors. Authorities seized over 100 of his works, and one drawing was publicly burned. Though he was ultimately released after serving a brief prison sentence, the damage to his reputation lingered. Schiele’s refusal to idealize the human body made him a target of moral outrage and legal suppression.

Photography, Film, and 20th-Century Censorship

The invention of photography and film in the late 19th and early 20th centuries introduced new ways to depict nudity—and new fears about public decency. Governments responded by enacting increasingly strict obscenity laws.

In the United States, the Comstock Laws of 1873 banned the distribution of “obscene” materials by mail. This included nude photographs, erotic literature, and even medical texts about sexual health. In Britain, artists like Aubrey Beardsley faced censorship for producing illustrations considered morally dangerous.

By the mid-20th century, film and photographic depictions of nudity were heavily regulated. Erotic content was often relegated to underground scenes, where it remained hidden from the mainstream art world.

Robert Mapplethorpe and the Culture Wars of the 1980s

Photographer Robert Mapplethorpe became a central figure in the modern debate over erotic art and public funding. His 1980s work explored queer sexuality, BDSM, and the male nude with stark, formal precision. While many praised his technical skill, others saw his work as provocative and obscene.

In 1989, Mapplethorpe’s exhibition The Perfect Moment was shut down after backlash from conservative groups. The controversy sparked a U.S. obscenity trial and ignited a national conversation about the role of government in funding the arts. Mapplethorpe became a symbol of the broader cultural conflict over artistic freedom, sexuality, and morality.

Today, his work is exhibited in major museums around the world, but debates over erotic art have not disappeared—they have simply shifted to new platforms and audiences.

How Impressionism Overcame Moral Censorship

Unlike many of the examples above, some explicit art survives simply because its movement becomes too popular to erase. While Impressionism is often associated with light, color, and landscapes, it also contained a strong erotic undercurrent.

- Edgar Degas’ brothel scenes and bathers depicted intimate, voyeuristic moments.

- Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings of Parisian prostitutes blurred the line between high and low art.

- Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe” (1863) scandalized audiences by placing a nude woman among clothed men in a contemporary setting.

These works outraged conservative audiences at the time, but Impressionism’s popularity ultimately protected them.

The case of Impressionism suggests that explicit art has a much higher barrier to survival than other forms of art. If it is considered valuable in other ways—technically, stylistically, or historically—it may persist. But when it is seen as purely obscene, it is far more vulnerable to destruction and suppression.

While some explicit art has survived censorship, countless works have been lost—either destroyed outright or quietly erased from art history. The double standard of what is acceptable and what is obscene continues today, shaped by changing social norms, corporate policies, and political agendas. Yet, history suggests that even the most controversial works can eventually find acceptance—if they are lucky enough to gain cultural legitimacy before they are erased

Leave a Reply